The Compromise of 1850 was made up of five bills that attempted to resolve disputes over slavery in new territories added to the United States in the wake of the Mexican-American War (1846-48). It admitted California as a free state, left Utah and New Mexico to decide for themselves whether to be a slave state or a free state, defined a new Texas-New Mexico boundary, and made it easier for slaveowners to recover runways under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

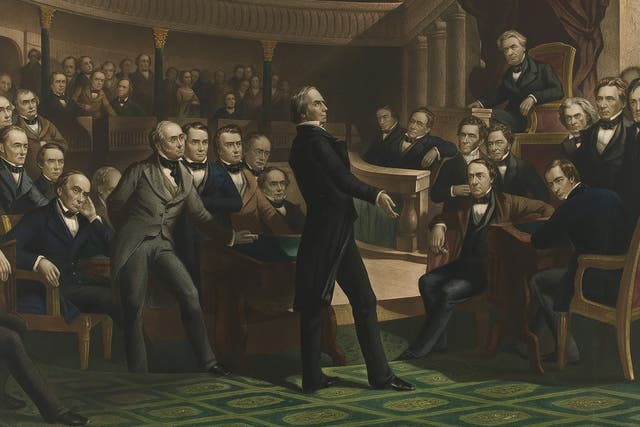

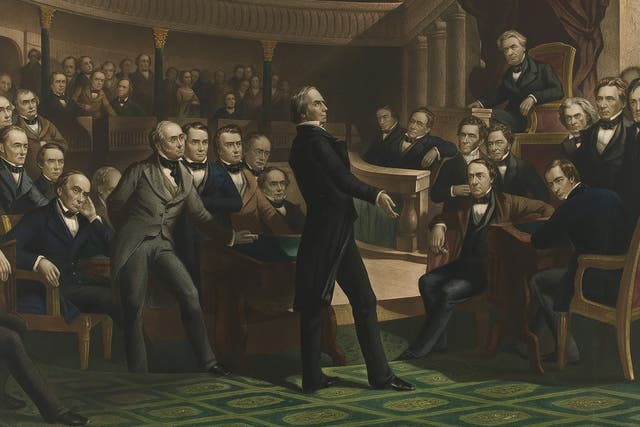

The Compromise of 1850 was the mastermind of Whig senator Henry Clay and Democratic senator Stephan Douglas. Lingering resentment over its provisions contributed to the outbreak of the Civil War.

Compromise of 1850The Mexican-American War was a result of U.S. President James K. Polk’s belief that it was America’s “manifest destiny” to spread across the continent to the Pacific Ocean. Following the U.S. Victory, Mexico lost about one-third of its territory including nearly all of present-day California, Utah, Nevada, Arizona and New Mexico. A national dispute arose as to whether or not slavery would be permitted in the new Western territories.

Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky, a leading statesman and member of the Whig Party known as “The Great Compromiser” for his work on the Missouri Compromise, was the primary creator of the Missouri Compromise. Fearful of the growing divide between North and South over the issue of slavery, he hoped to avoid civil war by enacting a compromise.

Famed orator and Massachusetts senator Daniel Webster, while opposed to the extension of slavery, also saw the compromise of 1850 as a way of averting national discord, and disappointed his abolitionist supporters by siding with Clay.

When Clay, facing health problems, grew too ill to argue his case before the senate, his cause was taken up by Democratic senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, an ardent proponent of states’ rights when it came to deciding the issue of slavery.

John C. Calhoun, a former vice president-turned senator from South Carolina, sought the expansion of slavery into new territories, but in an 1850 speech to the Senate, wrote: “I have, senators, believed from the first that the agitation of the subject of slavery would, if not prevented by some timely and effective measure, end in disunion.”

When the full compromise failed to pass, Douglas split the omnibus bill into individual bills, which permitted congressmen to either vote or abstain on each topic. The untimely death of President Zachary Taylor and ascendancy of pro-compromise Vice President Millard Fillmore to the White House helped contribute to the passage of each bill. Calhoun died in 1850 and Clay and Webster two years later, making their roles in the Compromise of 1850 one of their last acts as statesmen.

The Compromise of 1850 was made up of five separate bills that made the following main points:

The first Fugitive Slave Act was passed by Congress in 1793 and authorized local governments to seize and return people who had escaped slavery to their owners while imposing penalties on anyone who had attempted to help them gain their freedom. The Act encountered fierce resistance from abolitionists, many of whom who felt it was tantamount to kidnapping.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 compelled all citizens to assist in the capture of runaway slaves and denied enslaved people the right to a jury trial. It also placed control of individual cases in the hands of federal commissioners, who were paid more for returning a suspected slave than for freeing them, leading many to argue the law was biased in favor of Southern slaveholders.

Outrage over the new law only increased traffic along the Underground Railroad during the 1850s. Northern states avoided enforcing the law and by 1860, the number of runaways successfully returned to slaveholders hovered around just 330.

Both Acts were repealed by Congress on June 28, 1864, following the outbreak of the Civil War, the event proponents of the Compromise of 1850 had hoped to avoid.

An up-close look at the people, places and turning points of the American Civil War.